James Beard award-winning chef and self-proclaimed North Carolina seafood evangelist, Ricky Moore started cooking for others as a chef in the U.S. Army before graduating from the prestigious Culinary Institute of America. He worked in some of the country’s top kitchens from D.C. to Chicago, competed on Iron Chef America, and then opened Saltbox Seafood Joint in Durham, NC, in 2012. A tiny restaurant with a big reputation, Saltbox serves up Moore’s take on fresh local seafood. Inspired by classic roadside fish shacks of eastern North Carolina, the eatery features a menu that changes daily, depending on what’s in season. Moore authored his first cookbook in 2019, and in 2020, Saltbox was featured in the Museum of Food and Drink’s Black History Month exhibit.

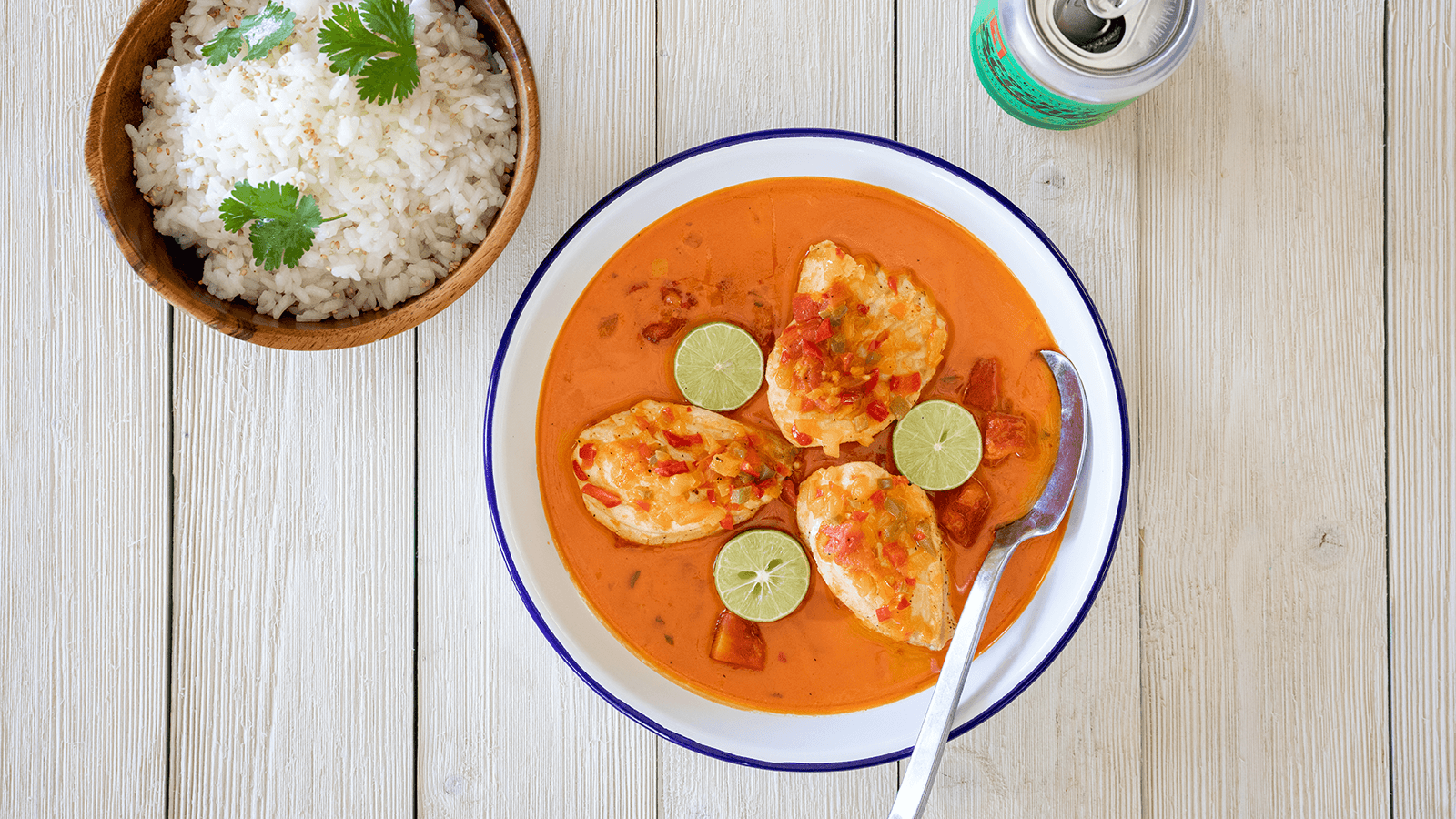

Chef Ricky Moore's Moqueca Recipe

Chef Ricky Moore's Moqueca RecipeQ: How did growing up on the North Carolina coast impact your decision to specialize in seafood?

I hadn’t explored seafood exclusively as a chef until I opened Saltbox Seafood Joint. But the moment I rolled up on the location in downtown Durham (where we first opened), it reminded me of a place where I used to get hot seafood in my hometown of New Bern. It just felt like the most organic thing to do in that location. There have always been a number of seafood restaurants in Durham, but I felt there was an opportunity to really dig in and bring that experience back to the forefront.

Q: You’ve called yourself the “evangelist of North Carolina seafood.” What does that mean to you?

Local seafood is my gospel and always has been, which is why it was such an honor to be named Best Chef Southeast by the James Beard Foundation—the ultimate recognition for honoring my culinary heritage and the place I call home. My vision and goal are crystal clear: to source the freshest local seafood from North Carolina fisherpeople and prepare it with integrity in a manner that celebrates the regionality of our coastal cooking.

Q: Before pursuing culinary arts, you wanted to pursue graphic design and visual arts. What role has your interest in art played in your cooking?

Every artist has a point of view and unique style that is driven by their creative energy to push the boundaries by consistent hard work. Being a chef and cooking is very similar; it’s a creative process that requires vision and giving it your all, day after day.

Q: As a child and as a member of the Armed Forces, you’ve traveled all around the world. Are there any places or regions that inspire your cooking?

Every place I’ve gone to, I’ve picked something up, be it an idea, ingredient or technique. But if I had to pick one place that has inspired me the most, I’d have to say Singapore—in particular, the wet markets, where so many cultures come together through the connection of food and where each vendor specializes in one or a few dishes. You can eat very well at an incredible value, and the quality of the ingredients is excellent. You go to one stall for fantastic noodles, then another for black pepper crab, and each dish has been perfected after cooking them over and over again. Those seafood stalls reminded me—in a way—of the fish shacks that used to be much more common across the Carolinas.

That was my vision for Saltbox—to open a small seafood-focused place with a limited menu using the best possible ingredients, prepared properly day after day.

Q: February is Black History Month and a great time to discuss the contributions of Black Americans to American history and culture. Who are the Black chefs who inspire you?

From a historical perspective, I really admire Edna Lewis, Patrick Clark and Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor, who might not be as familiar to folks. She was an American culinary anthropologist, griot, poet and food writer, born into a Gullah family in the Lowcountry of South Carolina. She moved to Philadelphia as a child and later lived in Paris before settling in New York City. Back in the day, she had a program on PBS called Vertamae’s Kitchen. To my knowledge she was the only African American on PBS, talking about Lowcountry cooking specifically.

And I can’t answer this question without mentioning Joe Randle, who I consider my triple OG. He started a cooking school in Savannah, GA, and later organized an event called Taste of Heritage, which showcased African American chefs and their contributions. He would travel the country and host dinners highlighting the rich heritage of African American cooking and its contribution to American cuisine.

Q: How do you use food and cooking to honor Black history?

I think it’s important to show the influence African food has had on our food culture in the Americas—and not just the United States. And by that, I mean the Pan-African global influence of the Atlantic Slave Trade—specifically where slaves landed in the New World. Every year in celebration of Black History Month, I feature a special menu of dishes at the restaurant that tell the story of how they influenced and interacted with the food and culture of these places. It’s important that we give credit where credit is due, and this sort of delicious research also helps us understand more about our ancestors and their lives, challenges and triumphs. There’s so much to be celebrated and understood!

Q: Do you have any pro tips for preparing seafood that you can share with us?

If you’re going to clean and filet a fish, don’t remove the scales first. Leaving the scales on makes it easier to remove the skin. It’s sturdier and also prevents you from cutting through the skin.

Q: As a world traveler, but also a coastal North Carolina native, what are some staples in your kitchen?

Olive oil, bacon fat, anchovies, various vinegars, capers and Dijon mustard. Lemons, shallots, garlic, onions, carrots and celery. I always have two kinds of mayonnaise—Duke’s and Kewpie—lots of hot sauces, smoked paprika and Old Bay. Plus, fresh eggs, of course, flour for making pasta, grits, corn meal and locally grown rice.

Q: Do you have any advice for aspiring chefs and restauranteurs?

Talent is necessary to get in the door, but 90% of success is consistent hard work. And sometimes talent is overrated. You need to have endurance to be able to run the race. But it’s also important to be able to recognize when it’s time to step away and reinvent yourself.

Define that this is the work you want to do early on and be alright with taking the hits when things don’t always work out.

Never forget that this is the hospitality business, which means that your primary responsibility is to make folks happy. But to do that, you have to be happy first.

And lastly, the chef/restaurant operator and the customer are in this together. It’s a shared experience. We need to engage and find that shared common space where everyone is having fun.

Q: What was the inspiration behind your Moqueca Baiana recipe?

Moqueca is a fish stew and one of the classics of Brazilian cuisine. There are two versions, one is found in the North and the other in the South, each influenced by the cooking habits of each region. In the North, Moqueca Baiana has elements of African culture, while in the Southeast, Moqueca Capixaba is heavily influenced by the Portuguese and Spanish. Both include garlic, tomatoes, cilantro, onions, salt and olive oil. The difference is that Moqueca Baiana also calls for dende oil and coconut milk—ingredients that are not part of the capixaba version. Dende oil (also called palm oil) is indigenous to Africa and is commonly used for frying and for imparting a dark reddish color. The key element of this dish is the rich decadent broth, which comes from the dende oil and the rich coconut. My version uses a variety of fish and shellfish, whatever I think looks good that day, and is garnished with a chiffonade of collard greens cooked in olive oil, garlic and salt.

Q: What is your favorite fish or type of seafood? How is it best prepared?

My favorite right now is trigger fish, an offshore fish. It has a very mild, white buttery flesh. It’s interesting because it eats more like shellfish than a finfish. It has no scales, rather, a leathery thick skin. The way I like it is “on the shell.” This means that when I butcher the fish, I keep the skin on and cook it skin-side down on a hot charcoal grill, so it cooks in its own skin, much like a BBQ oyster cooks in its shell. This technique keeps the fish very moist. I serve it with olive oil, chili and lemon, and the flesh just pulls right off the skin.

I also like to give it what I call the "Rockefeller treatment,” whereby I cover the flesh side with a mixture of breadcrumbs, anchovy, caper, chopped shrimp and butter. I then cook it skin-side down on a hot grill. The compound butter/breading mixture gets all bubbly and crispy on top. It’s absolutely delicious!